|

Anatomical

Road Map:

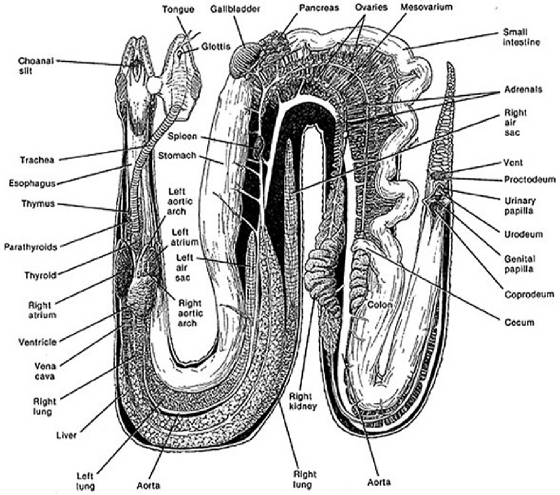

Because snakes are

basically one long tube, it is possible to partition their main anatomical

parts into sections. If you lay the snake out straight on a table with its head

on your left, going from left to right, the first 25 percent of the snake

consists of the head, the esophagus and trachea, and the heart. Those are the

major organs and parts.

In the second quarter,

about 26 to 50 percent of the snake, are the top of the lungs, the liver, and

then three-fourths of the way down the liver, the stomach.

In the third quarter,

about 51 to 75 percent of the snake, you encounter the gall bladder, the spleen

and the pancreas (or the splenopancreas depending on the species). Following this

triad of organs you will find the gonads (testes or ovaries). Coursing between

these structures is the small intestine, and adjacent to them is the right lung

(and in some species the left lung, as well).

In the last quarter, the

last 76 to 100 percent of the snake, you’ll find the junction between the small

and large intestine, the cecum (if present), the kidneys (right in front of the

left) and the cloaca.

Please click image below for larger view.

|

| Photo: Douglas Mader |

Outer

structure:

Most reptiles have four

legs. Snakes, however, do not have legs. They also lack a pectoral girdle

(shoulder bones) and — with the exception of the boids, which retain a

vestigial pelvis and external spurs — they also lack a pelvic girdle (rear leg

support).

Scales and Shedding / ecdysis: As with all reptiles,

snakes are covered with scales, which offer protection from desiccation and

injury. They can be smooth and shiny, such as a python’s scales, or rough and

dull, such as a hognose snake’s scales. The outer, thin layer is the epidermis,

which is shed on a regular basis. The inner, thicker, more developed layer is

the dermis. This dermal layer is filled with chromatophores, the pigment cells

that give snakes their color. Scales

are formed

largely of keratin derived from the epidermis. As the snake grows, which they

do their entire lives (growth just slows as they get older), this outer layer

of epidermis sheds off. New scales grow beneath the older outer scales.

Eventually, the outer layer sheds off, usually in one piece and inverted as if

it were a sock pulled from the top down. This shedding process is called

ecdysis. In general, if the shed

skin comes off in shards, it may be a sign of some underlying problem. The

snake’s health or husbandry issues, such as improper environmental

temperatures, humidity or caging furniture, might be to blame. Scales are attached to

each other by soft skin — generally not noticed from the outside — that folds

inward between each adjacent scale. Scales cannot stretch, but when a snake

eats a large meal, the skin folds are pulled out straight to expand the surface

area. Basically two types of

scales are on a snake. Its top and sides are generally covered by smaller

scales. These can juxtapose or overlap like shingles on a roof. The bottom of

the snake is covered by short but very wide scales that look like rungs on a

ladder. These special scales are called scutes. They form the belly of the

snake and are integral in the snake’s ability to move. Snakes have two eyes,

but they do not have eyelids. A spectacle, a transparent scale that is actually

part of the skin, protects each eye. When a snake undergoes ecdysis, it sloughs

this spectacle off along with its skin. Spectacles turn a light, semiopaque

blue as the snake prepares to shed. Herpetologists call this condition “in the

blue.” This is normal, but snakekeepers who have never seen it happen before

may mistake it for a problem. Immediately before the actual shed, spectacles

again become clear. This means that the shed is imminent.

It is imperative that

shed skin be examined every time a snake sheds to make sure these spectacles

come off. Occasionally one does not, and this results in a retained eye cap.

Like other shedding problems, a retained spectacle can be a sign of a health or

husbandry problem. In addition, if a retained spectacle is not removed, it can

cause problems with the animal’s vision and can potentially damage the eye. If you are experiencing poor or incomplete sheds; please refer to our care and maintenance section that addresses this issue. If snake has retained eye caps, please refer to the care and maintenance section that addresses this issue.

Head Features:

A

snake’s head contains the eyes, nostrils, mouth (and structures within), brain,

and a special sensory structure called the vomeronasal or Jacobson’s organ. Its

paired openings are just in front of the snake’s choana, the open slitlike structure

on the upper inside of the reptile’s mouth. All snakes have a forked tongue.

When they flick their tongue, the tips pick up minute scent particles in the

air and place them in direct contact with this organ. In essence, this is how a

snake smells.

Snakes’

teeth line the inner surfaces of the upper and lower jawbones (maxilla and

mandible, respectively). Nonvenomous snakes have four rows of upper teeth: two

rows attached to the maxillary (outer) bones, and two rows attached to the

palatine and pterygoid (inner) bones. Only two rows are on the lower jaw; one

is attached to each mandible. Most venomous snakes substitute fangs for the

maxillary teeth. These fangs can either be in the front of the mouth, such as

in a rattlesnake, or the back of the mouth, such as in a hognose snake.

Snakes

use their teeth for grasping, not chewing. Their teeth are recurved, so once a

prey item is bitten, the only direction for it to move is toward the snake’s

stomach.

Snakes have two eyes, but they do not have

eyelids. A spectacle, a transparent scale that is actually part of the skin,

protects each eye.

Snakes lack an external

ear, but they do have an internal ear, and they are capable of detecting low

frequency sounds ranging from 100 to 700 hertz. (A young person with normal

hearing can hear frequencies between approximately 20 and 20,000 hertz.) A

snake’s inner ear also allows it to detect motion, static position and sound

waves traveling through the ground.

Another external feature

found in boids and crotalids are the labial pits, a series of openings along

the upper and lower lips that contain heat-sensing organs. These pits help

snakes acquire prey, and they warn them of possible predators nearby.

|

|

| Photo: Douglas Mader Desription: Living Art Reptiles |

Vent / Cloaca:

All

snakes have a single vent, which is an excretory opening. This vent opens on

the bottom of the snake near the tail and leads into a compound structure

called the cloaca. The picture below shows the cloaca as well as the snakes

spurs. This is an example of a healthy cloaca which directly ties into our care and maintenance page on selecting a healthy Ball Python.

|

|

| Photo: Living Art Reptiles |

|

|

| Photo: Living Art Reptiles |

|